Women are the canaries for what's missing in apprenticeship.

In trying to roll back equity and nondiscrimination apprenticeship, DOL highlights the need for equity and nondiscrimination in apprenticeship. But what would really fix the problems?

The issue

Government data show that women enroll in government-recognized apprenticeship programs at a rate more than 30 percentage points fewer than their average participation in the overall American workforce.

The government’s evidence has flaws, but there is enough to suggest women signal bigger issues in the current build of Registered Apprenticeship.

Explain.

If there is a main character in federal workforce programs in the last two decades, it’s Registered Apprenticeship. Workers get paid to do the job right away and get better at it over time through on-the-job training, which makes it a politically preferred method of getting people into workforce as political leaders and workers sour on college.

This month, the Trump Administration highlighted data showing that half of all American workers—also known as “women”—have concerningly low participation in Registered Apprenticeship. It did so in part through the Trump Department of Labor’s justification to eliminate rules meant to raise women’s participation in Registered Apprenticeship.

From last week’s new Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional Occupations grant funding solicitation:

Currently, [97,175]1 women are enrolled in Registered Apprenticeship Programs nationwide, pursuing earn-and-learn experiences across a diverse spectrum of occupations and industries.

Emphasis mine. And from a July 2 rulemaking,2 which would eliminate the affirmative action and universal recruitment requirements for Registered Apprenticeship, along with killing an apprenticeship-specific requirement to not discriminate (something I’ll unpack a bit more below).

As of Fiscal Year (FY) 2025, the registered apprenticeship system supports 678,014 active apprentices nationwide. . . . While construction remains the largest sector for apprenticeships, accounting for approximately 244,858 active apprentices (about 36% of the national total), there has been notable diversification. As of FY 2025, more than 430,000 apprentices are now training in non-construction sectors, including public administration (149,782), educational services (83,777), manufacturing (30,479), and health care and social assistance (18,824). These trends point to growing interest across a wider range of industries—but also highlight where barriers to entry may be limiting broader adoption.

Emphasis mine again. Taken as written, the data shared by DOL show that women make up only around 14.3 percent of registered apprentices. The good news is that I don’t think it should be taken as written.

DOL’s apprenticeship data on active apprentices are extraordinarily messy and noisy due to misclassification of apprentices by sector based on the sector of the sponsor of the apprenticeship program. This means the organization that operates the apprenticeship program, which isn’t always an employer.3 For example, it counts the United States Military Apprenticeship Program, or USMAP, as “Public Administration.”4 That’s an overwhelmingly male program—77 percent men, more or less—that obviously skews apprenticeship read outs for a public sector civilian workforce that is 57 percent male.

Similarly, the DOL data misclassify several programs as “Educational Services” when they are really trade and manufacturing apprenticeship programs sponsored by technical schools and community colleges. In other words, the diversification of sectors discussed in DOL’s Federal Register notice, excerpted above, probably isn’t that much of a diversification because the way DOL has classified its data is a big mess.

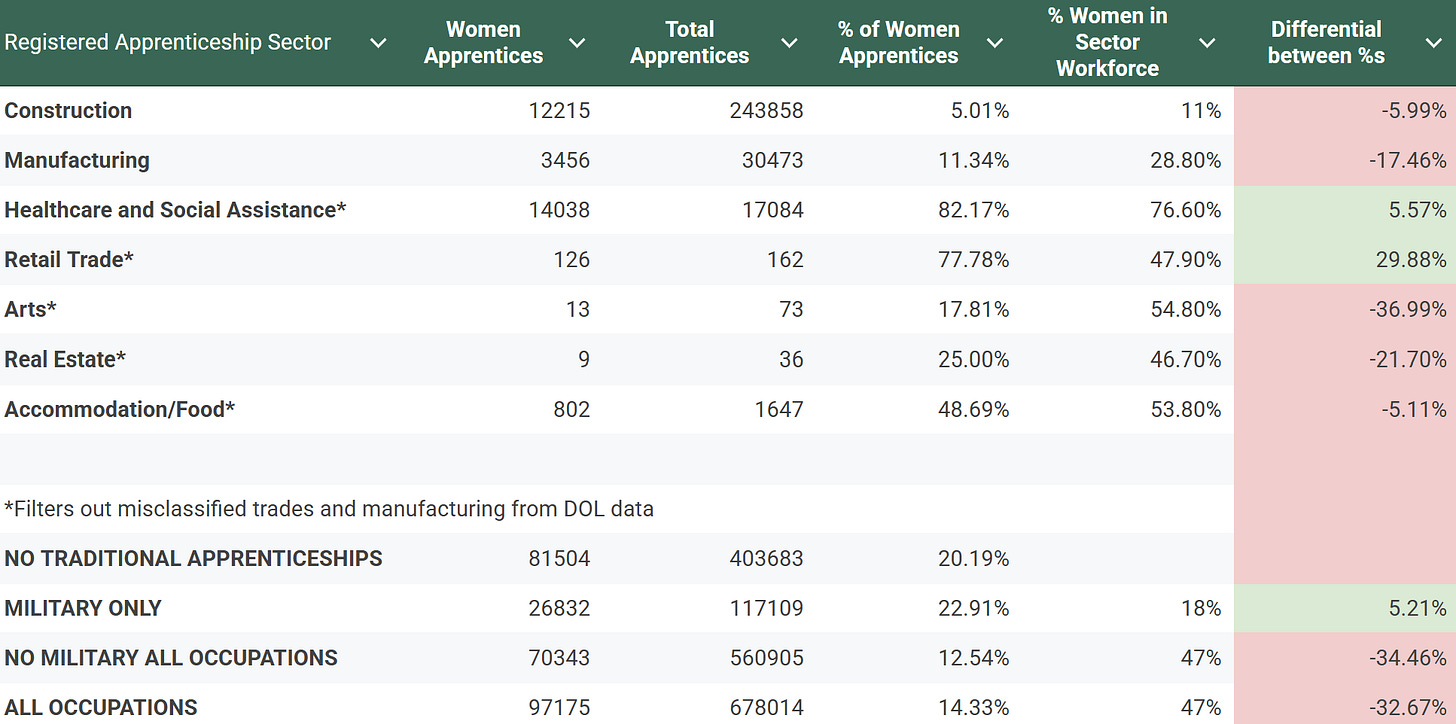

I spent several hours trying to clean this data as best as possible. Here is what “cleaner” counts look like, with top-level data with and without USMAP. I also include percentages without what I would consider the “traditional apprenticeship” sectors of construction and manufacturing.5

The bad news, then, is that the relatively cleaned-up data actually look worse for women. As you can tell, the predominantly male military apprenticeships pull up the percentage of women apprentices.

The current antidiscrimination rules do look like they had some significant impact. The overall percentage of women in Registered Apprenticeship increased from 6.21 percent (without USMAP) to 8.65 percent (with USMAP) to between 12.5 and 14.3 percent. That’s something, but considering we’re closing in on 100 percent Registered Apprenticeship growth since 2015, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to want the number of active women apprentices to have grown more, too.

Why is this happening?

On one hand, these data points confirm an old policy story about women in apprenticeship, which is that women are best represented in apprenticeships that don’t lead to jobs that make the most money, as captured in this Urban Institute report prepared for DOL’s Chief Evaluation Office. Above, this is supported by the outsized number of women in healthcare jobs and apprenticeships that tend to be lower paying than the trades and manufacturing jobs.

On the other hand, it also looks to me—even with all the messiness and noise in the data, and there is a lot of it—that something is off with women in apprenticeship. Yes, the apprenticeship participation figures are smaller than the trades, but women are underrepresented in apprenticeship programs in food and accommodations compared to their overall participation in the sector. Even in the “traditional” apprenticeship sectors where they are very underrepresented, the percentages of women apprentices fall well behind women workers’ overall participation in the sector.6

That’s discouraging. The current apprenticeship antidiscrimination rule, adopted in 2016, was targeted to improve women’s ability to access higher-skilled jobs via apprenticeship. In addition to the recruitment and affirmative action requirements, it included mandatory anti-harassment training to try to disarm the gnarly situations women face in those “traditional” apprenticeship jobs.7

One big reason I think its impact was dulled is that the antidiscrimination rule went into effect amid in the handoff between the Obama and Trump I administrations. This means it never really got a fair or dedicated implementation. I do think some of the gains you see owe to the rule’s efforts to recruit more people to apprenticeship. Yet, as Trump II’s proposed repeal points out, there has been virtually no enforcement of the rule. Frankly, I’m doubtful that DOL has ever had the apprenticeship staffing to enforce the rule as written.

Beyond the administrative piece, however, it’s not unreasonable to think that Registered Apprenticeship itself might be part of the problem with women’s lower participation in these programs. There is not a “No girls allowed” provision anywhere in current DOL rules—I double checked—but when you pair the constant weight of discrimination against women with flaws in the apprenticeship model, it’s understandable why women might not be making it into programs or sticking around.

First, a model built and reinforced by men in its most lucrative positions involves demands that do not necessarily sync with all that society expects and places upon women. For example, women head the overwhelming majority of single-parent households, which have grown in recent decades. They also take on the vast majority of organization and management in two-parent households. The best-paying apprenticeships—which remain in the trades and manufacturing—can involve hours at times that don’t sync with the smooth operation of either assembly of household. It can be hard to find childcare in those hours, and apprentices also may have to attend classes outside of work and school hours.

Pile that on top of the crap you may get from your co-workers and bosses for being the only woman in the job while having to get these dang kids fed and asleep,8 and yeah, it might not sound so attractive to try to be a pioneer in a traditionally male-dominated field that might eventually pay well.

The “eventually” also is part of the problem: all that that crap women take to be in the more lucrative Registered Apprenticeships could be for a job that starts and lingers around the minimum wage, which cannot cover cost of living in any state. Registered Apprenticeship rules only require that the starting wage be the federal, state, or local minimum wage, which I think is a liability to its long-term growth. Based on what I have seen, it’s definitely sabotaged the use of Registered Apprenticeship as a solution in fields where employers are begging for skilled talent yet can’t seem to pull up wages from the floor because the rules don’t require it.

What do we do about it?

As I wrote in May when writing about the mythical “skills gap,” you can’t divorce the interest (and hiring) of workers in a particular sector from job quality. Registered Apprenticeship is kind of a sector unto itself because of its employment aspect and the unique features hardwired into the rule.

For its part, the Trump Administration isn’t worried about any of that. Its proposed antidiscrimination rule deletes the provisions aimed at improving women’s participation in Registered Apprenticeship. It also gets rid of a freestanding requirement not to discriminate against workers in apprenticeship matters, only prohibiting discrimination already barred by federal, state, and local employment laws.

Between the lines, the Administration’s theory appears to be that a glut of new apprentices will come in through speedier registration of programs and expansion of programs dodging the old rule’s requirements. But you can’t get more people into apprenticeship programs without getting more people into apprenticeship programs.

For the most part, Registered Apprenticeship is a good job, which key to the political pitch for it. “For the most part,” though, is not at “all.” That’s a liability for Registered Apprenticeship and its long-term growth, one for which I think women’s participation is a canary in the coal mine—since what makes it easier for women to work in a field tends to make it easier for everybody to work in a field.

Yes, where the starting wage is the minimum wage, Registered Apprenticeship wages must by law progress as workers gain skills. Unfortunately, I’m told workers must feed and shelter themselves and their families while they gain those skills. It’s hard to participate in a Registered Apprenticeship if you’re making the minimum wage for a job where you might not be wanted because of who you are and that has nonnegotiable features that make it hard for you participate.9 Under the National Apprenticeship Act, DOL has the discretion to set a higher floor wage than the minimum wage for apprenticeship, which would sync with the quality framing of it the program and align with what the more lucrative programs advertise as their starting wages anyway.

Wages aren’t all of the problem. One constructive criticism I have of the 2016 antidiscrimination rule is that it required programs go through a lot of procedure and analysis but didn’t have much teeth if they didn’t or they didn’t take any meaningful action. It requires a complex analysis of whether programs are doing a good job recruiting people who can fill out its roster, but didn’t really have any teeth to it. Something confirmed by the enforcement data for the rule. Even if it did, I doubt that DOL had the staffing to see it through.

My solution isn’t “Do the same thing with teeth,” though. I don’t think a bunch of procedure is a stand-in for making programs actually do things that bring more people into them. I have been in too many rooms with political and business leaders being obtuse that they don’t understand why women aren’t getting into good jobs—or acting like they haven’t ever heard of the concept. I’m not saying you have to rewire the hours of a factory so that women can get jobs there. I am saying, however, that a program is having trouble attracting people because of childcare, it ought to be proactive about it.

If you’re going to pitch Registered Apprenticeship as inherently quality—which many political leaders love to do—its core recipe probably needs to include wages and action steps that ensure they’re quality jobs. Because of everything placed upon them, the fact that women actually are in a job can show its quality.

Women aren’t participating in Registered Apprenticeship near as much as they could be. We should take the hint.

Next week: what do we do about Registered Apprenticeship?

Card subject to change.

I guess we can count that as a cliffhanger, albeit an unintentional one as news and life stuff piled up to delay my promised proposal for “fixing” Registered Apprenticeship. This is apt to be an apprenticeship-heavy few weeks at JOBS THAT WORK as a result, but given the Administration’s plans for apprenticeship (and its often conflicting action), it’s probably going to be an apprenticeship-heavy few years. Again.

It’s also going to be a busy few weeks here, I suspect. Some of it will get cleaned up in the usual Friday edition of THE MONEY, but I gather you’ll see me in your inbox more than I’d probably like over the next few weeks. Here is some of what I’m tracking for paid subscribers:

Based on current progress, we could get a House bill with workforce appropriations as soon as today. The Hill doesn’t seem to be fully honoring the Administration’s budget requests in other areas.

The secretaries of Labor, Education, and Workforce owe a report to the White House next week on what workforce programs they want to cut and which ones they want to change.

In April, the President tasked the Labor Secretary with building a version of Registered Apprenticeship for AI that didn’t involve registering apprenticeship programs. If we’re going to find out what that means, it probably will be soon.

In conclusion:

The WANTO funding solicitation said “more than 97,000.” For precision, I’m pulling the information from the Office of Apprenticeship’s Registered Apprenticeship dashboard. Because I spend quite a bit of this newsletter pointing out the problems in the data on this dashboard, it’s worth noting that around 10,500—or 1.5 percent—of all apprentices did not disclose their gender.

While traveling at the start of the month and tracking The Big Bad Bill Is a Gorgeous Gent Act, I missed that this rule was part of a massive DOL deregulation push at the start of July. My apologies, and I have updated Friday’s post on nonenforcement of the current rule.

One, thanks to Elyse Ashburn at Work Rise for flagging this to me on LinkedIn.

Two, just to acknowledge reality, and I feel terrible saying this because I adore my former colleagues, these data problems are mortifying. The material, as presented, is misleading as evidenced by the omissions and errors in DOL’s Federal Register notice, which I think were unintentional.

The data are too messy for me to claim they are representative, but as best as I could filter it, Public Administration without USMAP amounted to 32,673 active apprentices, of which 18.67 percent (or 6,100) were women.

There were 414,000 open manufacturing jobs in May. There are only 30,473 manufacturing apprentices, although it’s not impossible that you could find another 10,000 or so lurking in the misclassified categories. There is a way of reading this as Registered Apprenticeship isn’t serving manufacturing terribly well.

The other way to read the data is that this discrepancy shows what I got at in May, which is I don’t think the manufacturing industry’s issues in trying to fill these jobs owes to its underutilization of workforce development programs that can fill these needs, Registered Apprenticeship among them.

One contributing factor for the discrepancy in participation may be that women are mostly in lower-paying administrative roles in the construction sector. In 2019, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that 40 percent of all women working in construction were in office roles. Yet, after cleaning up DOL’s data, I found that the number of active women apprentices in construction in fiscal year 2019 was under 4 percent. The number of women working in construction in 2019 not in office roles was just under 7 percent.

Once you’ve read one case about a woman being told to pee off the side of a crane, you’ll never doubt the struggle.

Coincidentally, this sentence was written while I held a toddler who had refused to go to sleep for her mother.

And whatever wage women eventually get above the minimum is likely to be lower than their male counterparts. This was supported by Registered Apprenticeship research, but unfortunately it looks like the Administration has stripped it from the DOL website.

Great perspective as always, Nick. Is my understanding of legislative process correct that Congress (particularly the Senate) need at least some Democrats to pass any budget that makes substantial changes to WIOA?