We don't need more 'good jobs' definitions. We need to make them real.

We have too many job quality frameworks and not enough tools that make it easier to offer good jobs.

The issue.

We have more definitions of good jobs than tools for making them.

Explain.

At a high level, 2025 has looked like a step back for the decade-plus-long effort to help more Americans get ahead through good jobs—or jobs that pay and treat people well enough they can stay and thrive.

Good jobs don’t just help workers, they can help employers through cost savings and boosts to productivity. Good jobs also are a more efficient investment of workforce development dollars by placing workers in positions where they will stay longer.

The Trump Administration has cut billions in Biden-era federal investments that prioritized spending money toward good jobs, which I helped with in my last government role with the Department of Labor’s Good Jobs Initiative. The Trump Administration also has stripped good jobs from funding—even going so far as to take away language that prioritized getting safe jobs with living wages for homeless veterans—and rescinded an executive order that targeted federal resources toward good jobs. Meanwhile, large corporate employers have taken last year’s election as a signal to pull back on workplace flexibilities, benefits, and other things that could factor into job quality.

The good news about good jobs is that despite the evident political turn of the last several months, job quality isn’t dead, it’s growing, after several years of investment and work. A couple weeks ago, Jobs for the Future1 announced that between 2019—before the last administration’s job quality focus—and the start of 2025—after the end of the administration—there was an increase of about 14 million American workers with good jobs despite those workers facing barriers to getting ahead economically.

This jump backs up what I learned anecdotally from talking with workers who received training and placement into good jobs via Biden Administration investments.2 And as I have written before, I know of red-state government leaders still using job quality to get better performance of their workforce systems. I suspect there will be more gains, albeit quieter ones, in the years ahead.

Still, expecting a backsliding is reasonable, too. Something here will be hurt by divestment in job quality, fears from training programs getting people good jobs will cost them funding, and corporate headwinds against jobs built for people—and perhaps even some large pets.

So how do we keep making in progress?

One idea: move beyond defining job quality and start building ways to make it easier to do.

A quick (and incomplete) check by my Robot Research Assistant found at least eight new or revised job quality frameworks just this year. It found at least 16 from the last four years, not counting international frameworks.3 My AI didn’t count the now-deleted federal Good Jobs Principles, the eight-point framework I used in trying to rewire federal grants during my last couple years at the Department of Labor.

These materials can make defining job quality a lot of work. Some have more than a dozen subcategories, elements, or planks describing how to tell whether a job is good or not. Others have hundreds of pages of accompanying materials. As someone who spent a lot of time implementing a job quality framework throughout the federal government, I don’t think there is that much appreciable difference from framework to framework. They all boil down to paying people well, giving them benefits, treating them like they’re people and not interchangeable cogs, etc. Or, as I put it in less than half of the first sentence of this newsletter: “jobs that pay and treat people well enough they can stay and thrive.”4

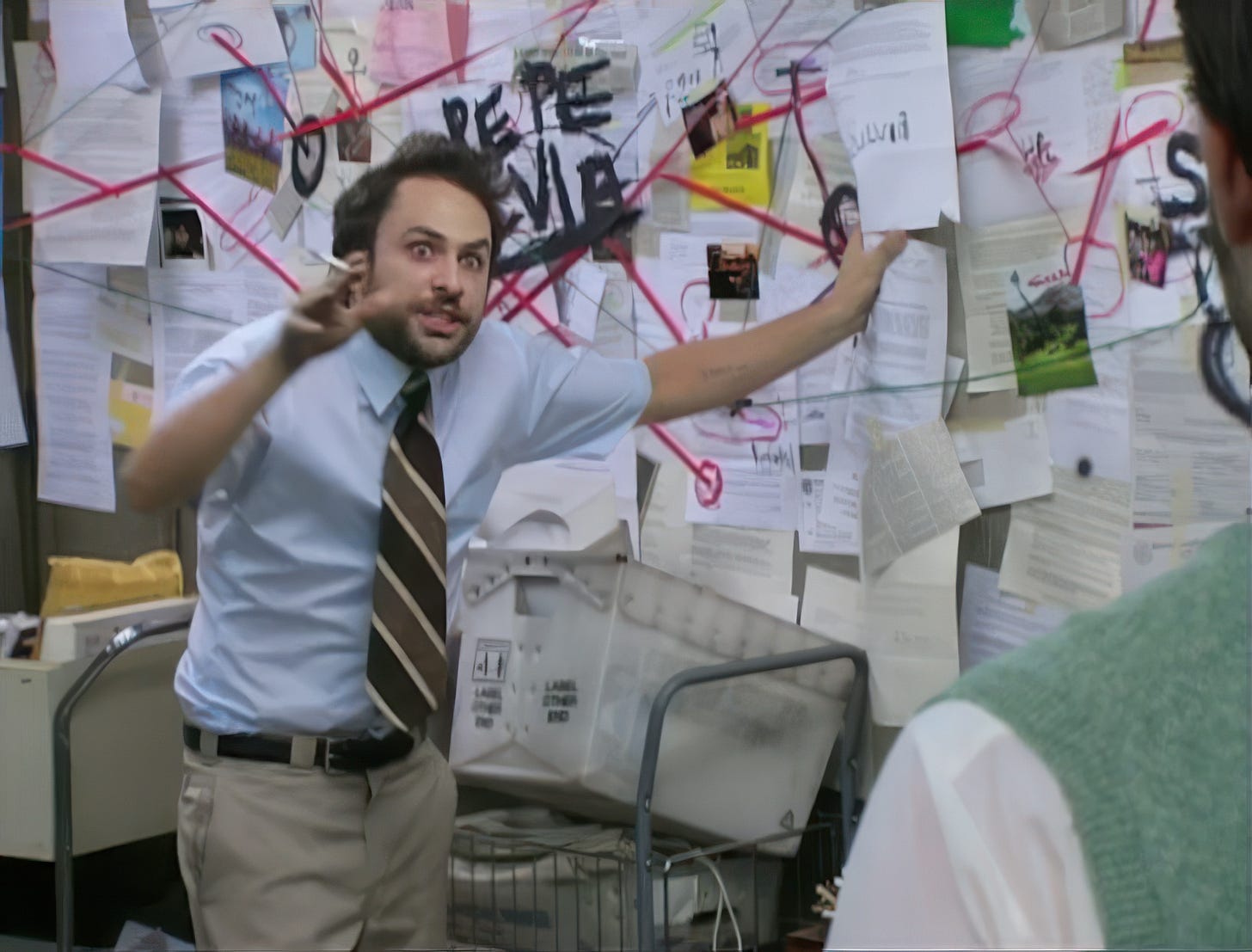

The problem is that even if the differences in frameworks are minor, other end users—employers and workforce providers—don’t take them that way. A few times over the years, I have had someone show me a matrix they made of the different definitions of job quality to try and sort out the differences. It felt a little like this:

That makes uptake less likely for a concept that employers can get skeptical of as soon as they hear the name. Employers, in addition to doing most of the employing in this country, also have to keep their operation running. It’s hard to sneak in new ideas into that mix, particularly if offering not-so-great working conditions was an early necessary evil in the early days of the business that the employer now feels like they can’t continue without.5 Thus, the more pages and words and details you throw at employers, the less likely they are to read it, let alone adopt it.

Which gets to the really hard part, one for which we have too few resources: tools6 for turning job quality definitions into practical steps that employers can and will take. Constructively, I feel like this is where some job quality documents say the work is hard and punt it back to employers to figure out based on their own needs.7

Good jobs definitely can be hard, and the work needed to make the real can be terribly individualized, but that doesn’t mean we can’t offer tools and insights that help where we know there are difficulties in creating good jobs.

What do we do about it?

I’m not going to tell people to stop writing their own job quality frameworks—sometimes people need this stuff in their own language—but I am going to tell you how to make those frameworks better and build tools and resources that make them easier to put into action. This was a big part of my last job at DOL, and I have Thoughts.

The focus of my recommendations is achievability. “Achievability,” however, does not mean “settling.” The bar doesn’t need to be lowered to the floor for everyone to get over it. If you build them a ladder, however, it will make it easier for everybody to elevate.

Offer a menu of what implementation looks like for each part of your job quality framework.

You shouldn’t write a job quality framework you don’t know how to implement in real life. I recommend giving employers and workforce organizations a choice of three or four options that, if taken, can satisfy (or help satisfy) one plank of your good jobs framework.

This type of specificity shows employers what tools they have on hand now to implement job quality and helps these concepts click for other people who might not get it. To help you build your own menu, I built a new version of a menu we offered at DOL, which is now scrubbed from government websites. You can find my new version here (for free).8

My menu is just a starting point for you to build your own, and I think it could be better and more tangible and specific. I don’t care what you put into your menu, but you should make it short and offer clear, tangible, and relatable examples of things that create a good job in real life.

Build explanations for how to offer good jobs in specific sectors.

We need more good jobs, but there are a lot of different kinds of jobs. It’s very easy for an employer (or a politician telling the employer what they want to hear) to say, “That isn’t possible in my sector.” Especially if, say, you’re recommending flexible scheduling, but the employer is a factory running three shifts a day.

I think we need more occupation- or sector-specific frameworks so employers and policymakers can’t opt out by saying “Those good jobs won’t fly in accounting!” or “You won’t ever see us do that in taxidermy!” or whatever.9

Craft tools to make it easier to do the harder, time-intensive parts of creating good jobs.

I think this is a spot where state and local governments can make some headway in the coming years, depending on their ambition and ability to invest. On its most basic level, what I mean are tools that show what the ideal living wage rate would be for a sector that matches each experience level or blank career progression charts that employers can quickly tailor to their business and workers. In other words, things that fill in human resources and related gaps that need to be filled to ensure good jobs can happen. The more point and click we make the nitty gritty of good jobs, the harder it is to say it’s too difficult to do.

If you’re feeling ambitious and can pay for it: you could set up off-hours childcare or pickup services for workers on swing shift, or offer state-supported supplemental benefits packages that make up for benefits an employer can’t pay for, but workers need to stay in a job.

Hello, valued customer.

Ten percent of every JOBS THAT WORK subscription helps older and other nontraditional nursing students find stable work by covering personal costs vital to getting them to class and into the workforce, through a supportive services fund I endowed to honor my mom’s workforce story—a big part of why I do what I do.

This week, I’m again closing out the quarter with a special group paid subscription sale to put more toward the supportive services fund that honors my mom. Through next Monday, if you buy more than one annual subscription, you’ll get a 20 percent discount off the normal cost of an annual subscription (two subscriptions for $80 each, three subscriptions for $240, and so forth). Buy more and you eventually start getting annual subscriptions for free.

The next three months could be awfully consequential to the future of workforce development in the United States. Paid subscribers get exclusive updates when Big Things Happen, my weekly cheat sheet in THE MONEY, and other cool things I have in the works, like the suite of resources I mention in today’s notes and insights for navigating a potential summer workforce grants blitz.

You can buy group subscriptions here.

Card subject to change.

Sorry for a second straight week of switching topics on the fly, but man, after Friday, I wanted to take a break from workforce system arcana and talk about something a bit more practical.

FRIDAY: The one workforce grant the federal government still pays out regularly. Yes, the Trump Administration is trying to end it.

NEXT TUESDAY: America can do better at helping veterans get employed.

There was going to be a study of the effectiveness of the work I did partnering with DOL agencies to expand job quality investments through their grant projects. My understanding is the Trump Administration quickly killed this study shortly after the switch in administrations.

In other words, I would love for there to be an actual empirical grade on what we did right and what we could do better, but to my knowledge, all we have is anecdotal evidence due to the Administration’s cutbacks.

One, I gather a reason for all the revision is to avoid the Trump Administration’s war on its (still-undefined) concept of “DEIA.” I’m understanding of that pullback, but at some point, you can’t do any work to improve access to good jobs without something that is likely to trigger the Administration’s sensitivities around “equity,” even if it’s not actually equity but common sense for helping people get ahead.

Two, I’m deliberately not linking to specific frameworks because the point of this newsletter is not to call people out, but nudge toward the next direction that this work should go. Reasonable (and unreasonable) minds may differ in my decision, but I think my approach is more productive than making someone feel like crap for trying to do the good work of good jobs. Someone had to write all these things, and I don’t think their hard work is the problem.

A couple reasons I really like my short definition, which you, of course, are under no obligation to use:

“Treat people well enough that they stay and thrive” tends to include a lot of stuff fleshed out to the Nth degree in other good jobs definitions. Call me crazy, but if you don’t hire people because of their race, or you have a multilevel conspiracy to thwart organizing rights, or you have a paranoia-based culture with frequent spying on workers, you’re probably not treating people well enough that they stay and thrive.

I single out pay because there is a certain class of politico who loves to try to fuzz up what is a good job by pointing out that good jobs are really in the eye of the beholder. That’s true, but the eye of that beholder is usually attached to a mouth that enjoys having enough money to feed itself and a head that enjoys having a place to sleep at night. You can quibble with the other components, but financial security is nonnegotiable.

Which is bad!

During my research, I did find a link to a tool that appeared to offer to walk employers through how to create good jobs at their organization. It looks like the organization pulled down that tool.

This is a broad statement and there are quite a few frameworks out there, as I highlight in the main text. If you feel like this misreads your organization’s job quality resources, please note that this is most likely a result of there being too many things to review and not a personal slight by me toward your organization. And if you have some cool job quality implementation strategies you’d like me to highlight in a later newsletter, email me at nick@jobsthat.work.

Eventually this will join a JOBS THAT WORK suite of workforce and job quality resources for paid subscribers.

I will remind you that unionization is the killer app of job quality, although I acknowledge it may not be a fit for a three-person firm.