It’s a weird time for apprenticeship. Can states help fix it?

At best, federal stats suggest the current situation is kind of a mess.

The issue.

Apprenticeship is in a weird spot. Official statistics on its growth signal a big problem if they’re right and create a different set of worries if they’re wrong. The Trump Administration seems trapped between its big intentions and the policy limits of its politics.

Can states pick up more control of the future of apprenticeship? And what has to change to really make that happen?

Explain.

The second Trump Administration has committed to reaching one million active apprentices.1 In July, the Department of Labor said that “[s]ince the beginning of the Trump Administration, more than 145,000 new apprentices have registered across the nation.” In August, the White House said that figure was 183,000.

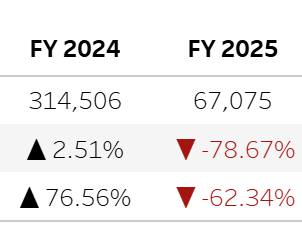

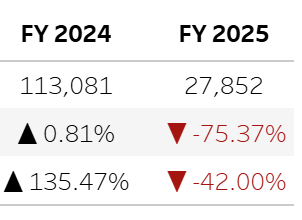

Yet, DOL’s official apprenticeship statistics show only 67,000 new apprentices for the fiscal year ending in a week—and that the United States is seeing its first decline in the total number of active apprentices since the pandemic. The total number is only a 1,100-worker year-over-year decline—and still a nearly 90 percent increase over 2015 figures for active apprentices—but there also is what appears to be a massive drop in DOL’s reported number of workers who have completed apprenticeships. Below, I screenshot all of these figures.

I have doubts these numbers will stay this low, and folks who have a lot of history with these numbers cautioned that DOL’s apprenticeship data aren’t always reliable, something I wrote about in July while cleaning up that data to get a better sense of women’s participation in apprenticeship. The reporting of state data remains a mixed bag and it can take a while for state statistics to find their way into DOL’s database.

Still, there is an obvious question about why there is a nearly 116,000-apprentice difference between the White House’s August tally of new apprentices and DOL’s figures from a month later. Even assuming the White House figure (183,000) isn’t reflected in the 67,075 new apprentices on DOL’s website, the combined figure—about 250,000—is still more than a 20 percent decrease in the number of new apprentices compared to the last full fiscal year of the Biden Administration (314,506).

Let’s be clear: if these statistics are wrong—and contradict the White House by six figures—that’s also a cause for concern in Apprenticeship World and the employers invested in it, both of which are looking for reliability and consistency from the Administration.

In recent weeks, I have heard increasing frustration with the Administration’s seriousness about expanding apprenticeship in reaction to what it’s really doing in this space. The Trump Administration has chopped at $46 billion in infrastructure cash the last administration put into promoting apprenticeship, frozen or tried to kill feeder programs for apprenticeship, proposed to kill dedicated apprenticeship funding, and many, many, many other steps that could stymie apprenticeship growth.2 There’s also the issue of DOL staff cuts that have left some programs and states unsure of who to ask questions about apprenticeship—and probably impacts the timely entry and accuracy of the figures above.

All that is part of why I have heard more interest in states taking lead in the future of apprenticeship, something the Trump Administration has signaled too. The idea being that if the federal government isn’t a trustworthy or reliable apprenticeship partner, the co-administrators of apprenticeship might be.

The good news is that I think states that recently took on oversight have done well in expanding apprenticeship. The bad news is that bringing in more states is easier said than done under current regulations and creates new problems that could impact apprenticeship growth. On top of that, the Trump II DOL looks hemmed-in by White House politics that likely prevent it from making things much easier for states to take over control of apprenticeship.

Level set: the messy way America regulates and promotes apprenticeship.

As a reminder, we don’t really have a “system” for apprenticeship in the United States, just varying government structures that have been soldered together.

All regulation of apprenticeship in the United States is voluntary. The primary vehicle is Registered Apprenticeship, a century-old consumer protection device in which a government agency verifies that programs train people, pay them, and let them come home with the same number of digits they had when they left the house. It started in the states—in Wisconsin in 1911—before becoming federalized in 1937 with the National Apprenticeship Act.

DOL maintained those existing state systems by effectively deputizing3 them. If states show that they will register programs under laws that match DOL regulations, states can register “for federal purposes.”

Deputization sure isn’t easy, though. One of my roles during my time at DOL was working with states seeking to obtain or maintain state deputization. DOL can only deputize agencies if they’re set up to enforce DOL’s rules. Current DOL regulations, drafted by the Bush Administration in 2007 and 2008, requires that each deputized state’s laws “conform” to these rules, a standard read very strictly.

At the same time, the regulations do not really tell states how they’re supposed to get to conformance, and states often figure this out on their own. That can hamper bringing in new state apprenticeship agencies, particularly if, say, an eager part-time legislator makes a change on the floor that can’t be corrected until the next session a year later.

The downsides of de-centralization.

In recent years, a clutch of Southern states have sought and received deputization, making marked improvements in oversight compared to the overstretched federal staff for whom they took over this work. Based on my experience, they brought resources and give-a-damn to the work that helped quite a bit. It’s part of why I’m broadly supportive of their being more state apprenticeship agencies.

At the same time, centralization is kind of the point of the National Apprenticeship Act, which unified a patchwork of state apprenticeship schemes. Even with a conformance standard in DOL regulations, deputized states can have very different approaches to managing apprenticeship on the ground.

My understanding is that unpredictability is why some multistate employers are very much not interested in every state getting deputized. Under DOL regulations, states are supposed to recognize the registration of programs approved by DOL or another state, yet I understand the process of doing that remains unpredictable and not guaranteed. These issues present real barriers to employers trying out apprenticeship.

Still, I do think we need more states to take on oversight of apprenticeship, and I do think there is a solution to address the needs of large employers at the same time.

The problem is it’s really not built for the politics of the second Trump White House and its allies.

So what do we do about it?

One, if the official DOL apprenticeship statistics suck and don’t reflect the actual number of apprentices, that’s something that should be addressed if we’re serious about reaching one million active apprentices.

Two, as someone whose job was to help shepherd states through deputization, there is actually a relatively easy regulatory solution for helping states get and keep their recognition a bit faster. DOL should build and publish a model state apprenticeship statute and set of guidelines that new states can literally copy and paste if they need their legislators to adopt a statute or to self-diagnose needed fixes ahead of their required five-year check-in with DOL.

In an ideal world, this would be an appendix to DOL’s apprenticeship rules, with language on how to comply with state legislative style requirements—which can be nitty and require or ban words like “shall”—and keep or maintain recognition. In a less ideal but still pretty good world, DOL could issue this as subregulatory guidance.

In this world, I have my doubts any of the above will happen. Even if it makes it easier for states to take over their oversight, the model state statute approach removes the current blank canvas for how states can build their own laws. For Republican ideologues, including those in the White House, that’s probably a bridge too far because it looks like the federal government telling states how to make laws—even if it’s the best, most workable strategy for handing over more control of Registered Apprenticeship to states under the current regulations. Much like they took the wrong lessons from Utah’s welfare system, some Republicans on the Hill seem to have read local control over apprenticeship laws as the real secret to the success of recently deputized states, not those states’ investment and effort in improving apprenticeship.

Which comes to another good idea that won’t make it through the White House workforce filter for similar reasons: DOL should handle direct registration of programs by companies that plan to operate in three or more states. Yes, there needs to be local support on the ground, but those employers’ apprenticeships are national programs with national implications. State governments don’t have to think nationally because that’s not their job, and one of the points of DOL’s authority under the National Apprenticeship Act is to set nationwide standards.

One last thought: none of this is a real apprenticeship system. There are too many moving parts here, and that makes the product delivered too variable to seem like a safe bet to workers and employees. We need real infrastructure to truly expand apprenticeship, but I also don’t think that’s going to be on the table in D.C. anytime soon.

Card subject to change.

On Friday, I’ll have the latest on appropriations, shutdown, and whatever is going on here in D.C. I also will have an update on some of that missing apprenticeship money, including some awards I don’t think have been officially announced. Oh, and someone finally sued over SCSEP.

Next Tuesday, the need for broader thinking and options in an uncertain future of work, and the workforce politics tilted far, far away from providing it.

For a few months, the Administration had noticeably not specified that the one million goal was for registered apprentices. The first place I saw the commitment specify one million registered apprentices was in the prefatory text of a new workforce program performance dashboard announced in August.

One: for brevity purposes, I had to cut back a list of all the apprenticeship-frustrating things the Administration has done since February. That seems bad!

Two: the Trump Administration, of course, would dispute any questioning of its efforts to promote apprenticeship. One of the things I suspect it would point to the dashboard above, which aimed to add accountability to most of America’s workforce programs by measuring how often they feed into Registered Apprenticeship. The issue—and part of the frustrations I mention above—is that many of the programs measured were built and funded without any intent of routing workers into apprenticeships, which much of federal workforce funding tends to disincentivize because apprenticeships take longer to complete and cost more as a result.

I prefer to use “deputize” over the official term, “recognition.” It’s less technically precise but more understandable to readers getting to know Registered Apprenticeship and its structures.

Companies, in many cases, register to access incentive funding. Often it is much higher (per participant) in the states and lower at the federal level. But some states are very challenging to deal with and can take years for approval of new programs. The juice is not worth the squeeze. This system needs a real overhaul, it won’t be able to scale like this.

As you know putting together the pieces to make RA's work is a task since we do not have a national structure, sustainable funding, sustainable supportive services or the long-term commitment to make this work. Compare this to Europe. I do like the fact that when RA Programs work they do embed the training and education with the employer. In many professions (e.g., doctors) we provide a great deal of work-based learning but don't call it apprenticeship. Thanks for your great column, hope to cross paths one of these days at a state or national conference.