How to get smarter AI jobs projects.

A nuts-and-bolts breakdown of how funders can build workforce projects that work.

The issue.

It’s hard for funders to figure out how to tease out projects that effectively blend AI into workforce training. But I have seen one example of how not to do it—and I have an alternative.

Explain.

To a degree, I feel bad for policymakers when it comes to AI and jobs training. It’s hard to build any policy for emerging occupations based on quickly developing technology. Emerging jobs have to emerge enough that you can know where to point the training, but they have to be stable enough for a program not to train to a gig that won’t exist in a few months.

But good AI policy also has been elusive to capture due to political leaders’ fear of actually leading on the issue. On workforce, they have mostly deferred to employers who don’t really know the answers other than “We’re probably firing people” and tech CEOs more interested in hyping the job-killing power of their product—and its apparent unknowability for many workers beyond “AI literacy”—as part of AI’s sales pitch.

As I noted for paid subscribers on Friday, a few weeks ago the Department of Labor published a grant opportunity that its leaders talked up as requiring applicants to show how they will train young people in job-relevant AI skills. Substantively, it doesn’t really do that.

To explain why—and not just poke holes in somebody else’s work—I thought it would be helpful to walk you a little bit through the process of building a federal workforce funding opportunity and offer an alternative. This is a bit more mechanical than I usually am in this space, but I think it’s a good view into how policy actually gets built and a good example of strategies I think are helpful for all sorts of funders in trying to get better projects off the ground.

The tricky art of trying to get people to spend money in smart and interesting ways.

Let’s start with the fundamentals.

A funding opportunity is the document that the federal government posts to tell people that money is available, how to get it, and what’s expected if they do get it.1 At a 10,000-foot level, a funding opportunity tells the world the point of the project and gives applicants directions on what they need to put in writing to get it. Often, agencies grade applications on a 100-point scale based on how well they meet criteria that can include the substantive details of a project, the experience of the applicant’s team, and the steps applicants have taken to reduce any risks in investing in them.

A funding opportunity’s relevance doesn’t end when the agency spends the money. When the government makes an award, these documents often are incorporated into the agreement between the government and the grantee. That means funding opportunities ultimately commit grantees to produce the type of project the funding opportunity said the agency wanted to fund.

So, if the funding opportunity says to fund habitats for zebras, and the grantee funds espresso makers for capybaras, the language of the funding opportunity provides grounds for an audit and the government reclaiming misspent funds.

(And, you know, a signal to evacuate areas that might be besieged by overcaffeinated capybaras.)

Bound for The Floor.

When I was working with agencies in my last policy role, my first thought was The Floor—or the type of project that met our policy goals at the bare minimum even if a grantee did the least expected of them in running the project.

You can build The Floor by saying very clearly what the money can be used for and what it can’t be used for, but you also need to offer applicants a specific idea of what type of result you have in mind. Last year, I wrote about how one of my hacks was to give applicants menus that gave them tangible specifics on what type of project we wanted to fund. The menu let them know the flavors we wanted so they could cook up the right kind of project based on their own ideas. Or if they weren’t feeling so bold, they could just pick one of the items we put on the menu and say they would do that.

To offer an illustrative (and nonspecific) example of one way to write a menu into a funding opportunity:

The goal of this project is to help employers improve hiring processes to access skilled talent they may not have reached previously in their community. Applicants may do so through approaches including, but not limited to:

Assisting the employer in adopting skills-first hiring techniques.

Helping the employer identify colleges and academic institutions at which they have not held recruitment events and facilitating those events.

Advising the employer in a review of hiring procedures to see how and why qualified candidates might not get an interview.

The inertia problem.

A lot of organizations are frequent customers of federal workforce programs. That’s less a product of some sort of inborn corruption but a practical consequence of the frustrating lawmaking around these programs. Congress legislates many workforce programs into a phone booth, and those specialized requirements mean it’s a lot of work for a new organization to claw in.

It leads to some frustrating (but also understandable) institutional inertia. The usual customers are apt to outlast the administration in the White House and whatever trendy new thing it’s programming into a funding opportunity. In turn, some usual customers default to saying juuuuust enough about the new thing to get the points they need to win a new grant, then, when they get the money, focus on the same fundamental projects they’ve usually run. It’s understandable. The fundamentals have kept the organization’s doors open, not this new stuff. But it makes it hard for new features and ideas to sneak into these programs, even if they’re sorely needed.

Accordingly, I think you have to do two things to really make sure that a new round of federal projects aren’t just the same old thing. One is putting a large number of those 100 points behind whatever change you’re trying to make. The core functions of the program—those requirements Congress legislated into a phone booth—will always have to eat up a big share of points. But if you put, say, 15 to 20 points behind a new priority, the usual customers will have to adapt and integrate the new thing—or someone else will get the money.

The other thing you have to do is draft the document so that applicants can’t get those points just by giving lip service to the new thing. That means you have to give very clear prompts—or menus like the kind I mention above.

This is better illustrated than explained in a vacuum. Say you’re building a funding opportunity for a youth program that you want to transition from short-term trainings to apprenticeships. You don’t want to publish a prompt that lets an applicant BS their way through the section without thinking through or committing to actual change.

The wrong type of prompt is something like this:

Applicants will be expected to describe how their training will enrich the lives and lead to meaningful careers for young people, including apprenticeship. (1 point)

As drafted, this lets an applicant say “We’re going to give the kids some jobs training, maybe with apprenticeship, and it will be enriching for them and stuff” and likely get the point. One point is not nothing in a tight competition, but it’s also not likely to make programs with calcified features actually change what they do.

Instead, you want to do something like this:

Applicants will be expected to describe training that leads to meaningful careers through apprenticeship. Applicants must specifically show:

That they have the experience and capability to run an apprenticeship program through youth, including examples of any previously operated or currently operated apprenticeship programs for youth. (5 points)

That these apprenticeship programs lead to careers that are in demand in their community and hiring apprentices who are young adults. (5 points)

That the applicant has partnerships with employers who are committed to hiring young people as apprentices, as evidenced through letters of support or other appropriate methods. (5 points)

One way not to get good projects for AI skills development.

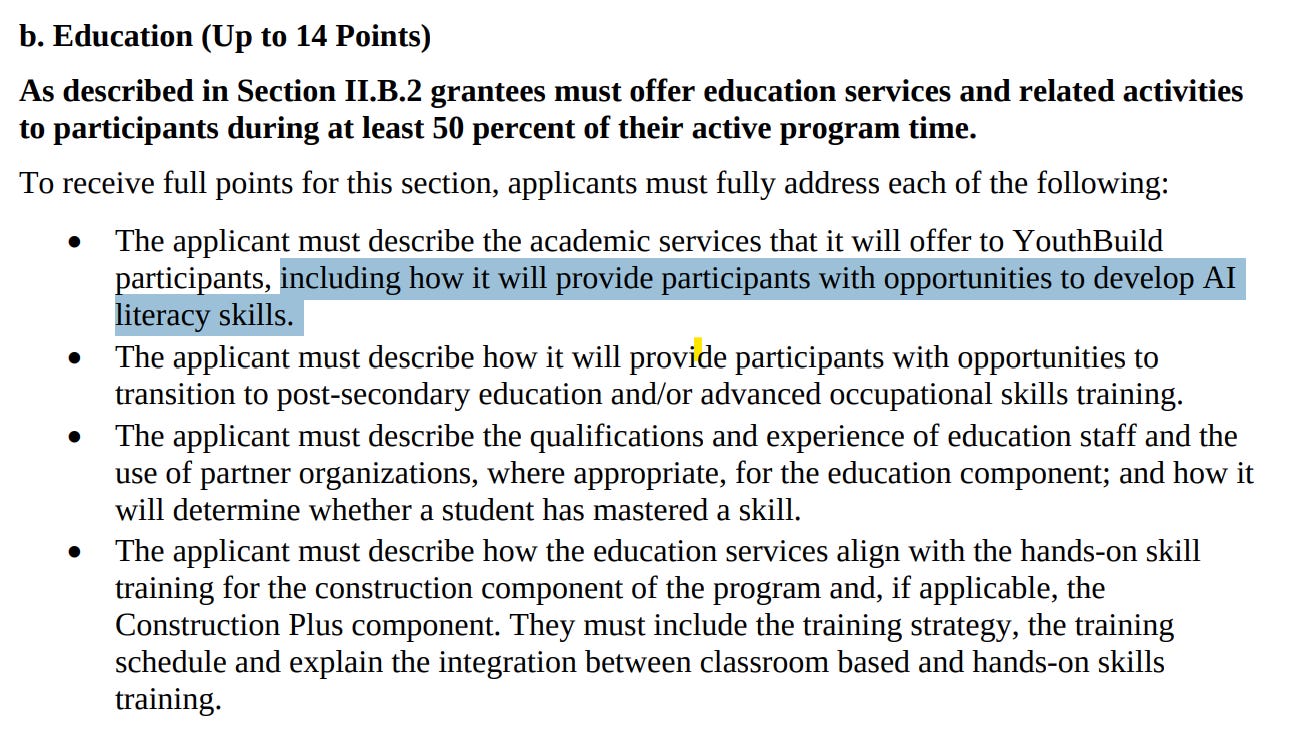

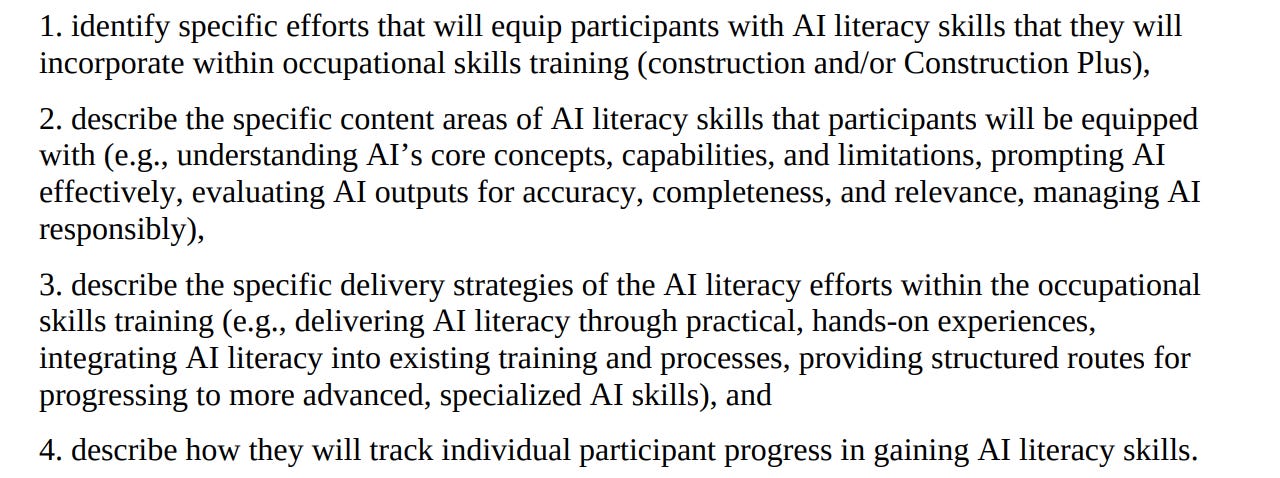

Which brings us to the YouthBuild funding opportunity that DOL published over the holidays. In rolling out the announcement, DOL talked up that the funding opportunity “advances artificial intelligence education for youth by requiring applicants to incorporate AI literacy skills in the education component of the program[.]”

For the uninitiated, YouthBuild trains lower-income young people to learn job skills and helps them find employment by having them construct affordable housing.2 Bringing AI into that type of program can seem like an awkward fit, but there are plenty of good uses for AI in construction and related fields. For example, it can help reduce time in measuring or identifying the right tools, assist in interpreting blueprints, and improve the quality of written materials authored by craftspeople that have learning disabilities or other barriers.

DOL’s text doesn’t get into any of that, and I think these projects aren’t likely to advance much of anything around AI education. The text highlighted below in blue describes the only required AI components that has to be in the applicant’s project. It’s not clear how many points out of 100 addressing this little mention of AI will get.

First, this leans on the low bar of “AI literacy”—which tech CEOs often explain as “Write better prompts into ChatGPT.” Second, it doesn’t explain what DOL means by “AI literacy” or what the types of skills DOL would like to fund, which leaves that open to interpretation, something that frequent customers likely will reasonably swing into something that looks like a typical YouthBuild project. Finally, the points valuation—and lack of clarity of how many points AI earns—also means that the usual customers of the program aren’t apt to put their backs into building a more robust AI strategy.3

There is a section for offering deeper AI strategy, but it’s optional, and it only earns an applicant one bonus point.

The last clause of the parenthetical in No. 3 is probably the best text here for avoiding applicants BS-ing their way through their strategy. But applicants aren’t required to address it, which makes it less likely they actually will.

So what would you do, smart guy?

As I have written about previously, researchers have found that the AI skills employers are hiring for are the skills key to integrating AI into existing fields, not just “AI literacy,” a concept that ultimately comes down to sorta knowing what AI is and how it works.

Accordingly, I took the idea of AI integration from research and and remixed DOL’s text with some of the concepts I detail above. The outcome is the below example (and not a definitive one, mind you) of a required AI application section for YouthBuild with significant points behind it.

Training young workers on AI skills (15 points).

The Department has determined that it is vital that YouthBuild train young workers in AI skills that will improve their ability to be hired and retained by employers as this vital new technology becomes more common in American workplaces. Accordingly, successful applicants will outline a thorough and complete strategy for teaching students AI skills and how to integrate it into the workplace as the technology evolves.

To receive full points for this section, applicants must describe:

A detailed classroom strategy for teaching AI skills. This strategy must describe how the applicant will provide regular and progressive instruction on AI in the workplace, discussing specifically how this approach will teach students appropriate uses for AI and how to adapt to changes in the technology. (6 points)

A detailed on-the-job training strategy teaching students on how to practically integrate AI in the process of constructing low-income housing. (9 points)

Applicants’ strategy must describe specific techniques for how it will meet this goal. These techniques can include, but are not limited to:

Showing students how to improve the efficiency of construction projects using AI tools, such as by harnessing AI for helping interpret blueprints or suggesting tools and techniques for handling construction tasks.

Helping workers with literacy or communication challenges access stable employment by using AI tools to produce required documentation for construction projects or similar strategies.

Using AI tools to scan and identify imperfections in work to correct deficiencies that might not meet local building codes and assist students in improving the quality of their work.

You might have noticed I don’t really use the phrase “AI integration” anywhere in this text—or at least not directly. I think it’s easier to get the point across to applicants if you don’t use phrases like “AI literacy” or “AI integration” and just say what you’re expecting to happen here. Those shorthands are useful and policy wonks tend to look for them to know whether they think your work should be taken seriously. Nice as it might feel to earn mild validation from some dude at a thinktank, policy wonks usually aren’t applying to this type of grant. Thus, those AI terms of art, alone, don’t actually communicate the government’s expectations about what the grant project should do, which makes it less likely an application will include information the government needs to make a good funding decision.

On that point, I lead off with a really clear statement of what the agency is trying to do with the money and why. This better clarifies for the applicant why you’re asking for this information and where you want the project to go. It also communicates the purpose of this section to the staff building application reviews—who might not be the same people drafting the funding opportunity—and the oversight staff who have to enforce the requirements.

One last thought.

There’s quite a bit more to explain around the edges, but if I was uninitiated on this stuff, I think the question I would have after reading everything above is, “Why doesn’t what DOL wrote look more like what you wrote?”

Well, I don’t know anything about the development of this particular grant, but if I had to hazard a guess, it’s de-risking a knotty political and logistical situation.

Like I wrote above, there really isn’t much clarity in how to train workers for AI jobs, or at least not anything tangible that has resonated with political leaders. That’s likely to make political decisionmakers uneasy to go beyond the low bar of “AI literacy”—or approve projects that actually dig into the specifics of AI jobs training—because it swims against the very loud narratives they’re hearing out of the tech CEOs talking at conferences. At the same time, there are fewer career staff than there used to be to run programs like YouthBuild, and the core features of the program installed by Congress are hard for anyone to oversee at current staffing and resource levels.

Plus, no matter the oodles of evidence to the contrary, there’s almost always a fear among everyone up and down the chain of decisionmakers that if you ask too much of applicants—even to get better projects—no one will apply. Over the years, I have seen grants with some really burdensome application requirements. When the competition was over, the government never had a shortage of organizations to give the money to.

Thus, despite its holes, DOL’s approach likely lets decisionmakers feel like they did something on AI in the “safest” way possible. AI gets mentioned, the smart applicants can go deep (and get an extra point!), and the agency doesn’t need to spend a ton of time training up oversight staff on something detailed and new.

If that feels dissatisfying, well, it is. It’s really not too far a walk from “safe” to better, and the American workforce kinda needs better more than it needs than “safe” right now.

Card subject to change.

I expect Thursday’s edition of THE MONEY will be loaded again as I get my arms around a busy start to the year in workforce. A few things you’ll probably read about, congressional nonsense pending:

The universities that appear to be showing up for Workforce Pell.

New accountability measures in federal workforce dollars.

Oh, and there’s a big scandal involving the Secretary of Labor and her spending habits—one that has sidelined key DOL decisionmakers. Seems bad. I’ll probably talk a little about it.

It’s also called a Funding Opportunity Announcement (or FOA) or a Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) depending on the agency.

Along with other types of skills training that I’m going to put off to the side to keep things simple for the uninitiated.

Something you might have thought reading this sentence: legally, DOL can’t write this kind of glancing inquiry into AI but aggressively grade down applicants who simply say AI will be part of the training and move on. By statute, an applicant can appeal DOL’s funding decisions for YouthBuild if it thinks it should have gotten the money but didn’t because DOL didn’t follow its own rules in grading the competition. Accordingly, DOL would be at a risk of losing in court if it published this “PLEASE SAY ANYTHING ABOUT AI” section, then graded applications as if applicants needed to include a deep treatise on AI and jobs training.